I had invited my son to join me on my journey to San Francisco’s Museum of Modern Art, but he turned me down. That actually ended up to be a good thing because if he had come along, he either would have a) gotten mad at me because I was taking too long, or b) caused me, out of guilt, to rush. As it turned out, I was able to spend almost three and a half hours working my way through the Joseph Cornell exhibit Naviagating the Imagination while lingering over every amazing box, collage, commentary, note, and scrap of paper. It runs until January 6, 2008, and I highly recommend hawking a piece of jewerly if necessary and taking the A-train to see it.

As I wandered through the exhibit, I wrote down notes (in pencil – no pens allowed in the museum) about what I saw into my notebook. What follows are those musings.

I started by watching a short film by Larry Jordan who lived and worked with Cornell for a while in his house in Flushing, New York.

Cornell’s House in Queens

from Freeshell.org

The film, entitled Cornell 1965 contains the only film footage of Cornell, and if you blink, you’d miss it. It’s not that Cornell was reclusive, as is sometimes implied, but that he wanted his work, not himself, to be recorded. Jordan was in the attic filming Cornell’s art work, when his camera happened to look out the window to find Cornell in his backyard, rummaging through boxes and trying to piece parts together, presumably for another one of his “object boxes” as he liked to call them. Towards the end of the film, there’s another glimpse of Cornell, standing inside his garage, hands on his hips, looking towards his yard. The camera lingers there, watching him lovingly, and you get this sense of a fleeting stolen moment, which was obviously very precious to the filmmaker.

Jordan narrates the film and gives us some insights into Cornell: Proust was his favorite writer. Debussey was his favorite composer. Lorca, a favorite poet.

Jordan said that Cornell “. . . believed that there were moments crystallized in feelings from the past . . .” He said that Cornell used the term “epiphanies” more than once to describe what he was striving for in his art and that “. . . his working concern was only to bring certain threads of reminiscence together.” Jordan also said that Cornell “preferred working with humble materials,” and that his simple little nine minute film was a sort of homage to that vision.

One of my favorite things from the exhibit was a huge blown-up photograph of one of the set of shelves from Cornell’s basement where he stored all his stuff and made his art. Rows and rows of boxes are stacked precariously on top of each other. The boxes are all different sizes and shapes and have handwritten labels on the front with descriptions such as “cornials,” “plastic shells,” “tinfoil,” and “tinted cordial glasses.” Apparently, Cornell liked to collect ephemera as a way to relax and break the tedium of his job as a textile salesman. It wasn’t until 1931 that he shifted from the hobby of collecting to making art from his collections.

He started in 1929 with collage and later moved on to boxes, which he called “poetic theaters.” And in 1953, he returned to making collages again.

Untitled (Tamara Toumanova) c. 1940

from Friday Prize

But it’s Cornell’s “cabinets of curiosity” for which he best know. The exhibit commentary says, “Cornell also absorbed his family’s Victorian sensibility of gathering and recycling things as talismans of ‘what else were scattered and lost.’ ”

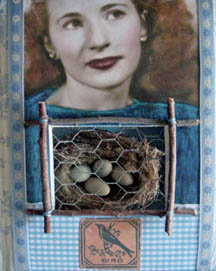

Untitled (Paul and Virginia) c. 1946 – 48

from the WebMuseum

Paul and Virginia is one of my favorite boxes. Although I had seen Cornell’s work before, I had never seen this piece. I love the light blue color throughout and the way every little edge of the box is covered with text or illustration from old books and magazines. It reminds me of the piece I did for my mom The Gift. Apparently, Cornell did not feel any compunction against using original source material in his work.

As I was standing in front of this piece, and man and his daughter stood next to me. The girl was about ten years old. She said something like, “Why did he use those bird’s eggs?”

The dad replied, “You need to think about what they represent.”

The girl wondered, “The beginning of life?”

Even at her young age, she got it.

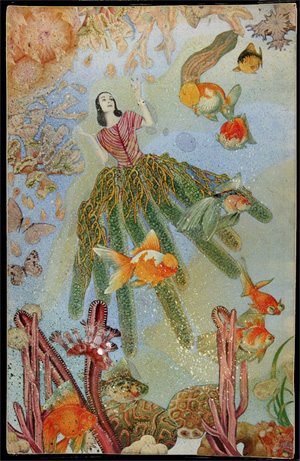

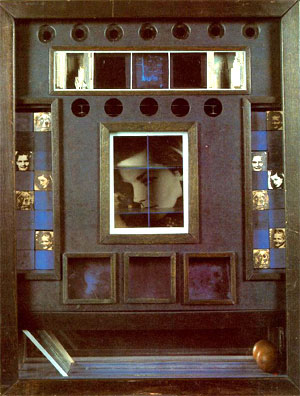

Penny Arcade Portrait of Lauren Bacall c. 1945

Apparently, Cornell loved to create works that would incorporate and pay tribute to the artistic gifts of people he admired, as he did with the piece for Tamara Toumanova, and in the one above for Lauren Bacall. He was inspred by her movie To Have and Have Not and the song she sings in the movie “How Little We Know.” In his notes for this “dream machine” he writes about wanting to create “. . . a machine that can capture over and over what one rememers from the film, more of the romantic ‘afterglow’ than literal scenes such as a musical composition which evokes and prolongs the pleasure and mood of an experience without being merely descriptive.” from Revised Notes on April 1945. You can definitely get a sense of the nostalgia that pervades Cornell’s work. There’s an interesting article at the Tate Research Center that talks about how Cornell’s passions for entertainers — ballerinas, opera stars, and actresses, to name a few — influenced his work.

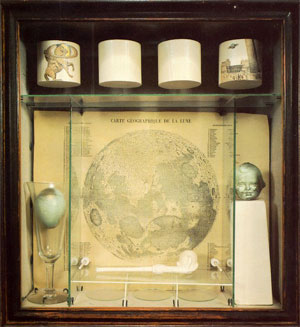

Untitled (Soap Bubble Set) 1946

from WebMuseum

Cornell like to use antique star maps in his work. He was an avid stargazer, and as the museum commentary notes “. . . celestial navigation became his primary metaphor for extended travel across time and space and between the natural and spiritual world.” He used Dutch clay pipes used for blowing bubbles in his work as possible reference to “pipe dreams” He wrote in his notes regarding a collection of images around the theme of air travel that “. . . the beautiful fantasy involved the early ideas of conquering the air, and some of the more fantastic continuations of such dreams.”

One interesting thing that I learned about Cornell’s work, is that he would create portfolios of magazine and news clippings, postcards, advertisements, and other printed material that he could find all relating to a particular person or theme that he was interested in. He was inspired to create a case of papers and ephemera referred to as GC 44 after working at the Garden Center Nursery in Bayside, New York in 1944. In his notes he wrote about the collection “. . . all this manner of thing are gathered to convey this fleeting glory the sunlight filling the kitchen to recreate the House on the Hill . . . the calm enjoyment vs. the former feverish wanderlust to be away forgetting the besetting reaction of physical and mental fatigue (which resulted, however, in endless experiences of unexpected beauty, precious moments of the commonplace transformed by a kind of magic producing the deepest and warmest kind of love for each humblest aspect of landscape and person encountered — in this territory where one felt so much a stranger and but a ‘few blocks from home.’ ”

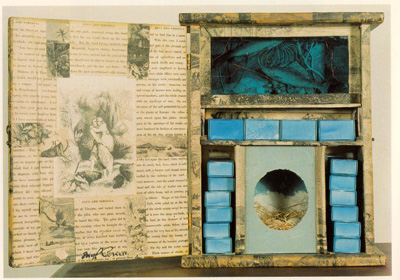

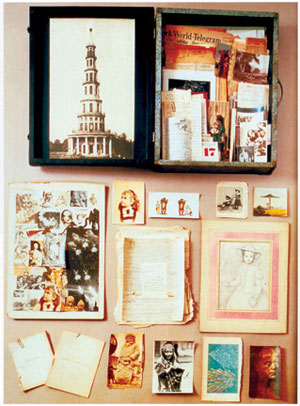

Crystal Cage: Portrait of Berenice ca. 1934 – 67

from The Warhol

Between 1934 and 1967, Cornell collected all sorts of material for a photomontage publication about a little girl named Berenice who would do experiments in a tower, or Crystal Cage. He eventually published this series in View magazine which you can see online at Bibliopolis. In his notes for this piece, dated November 14, 1942 and labeled “Appearance of Berenice” Cornell wrote about the sudden inspiration he had after seeing, through an elevated train window, a brief glimpse of three girls as they rode by. “. . . that little arm held a key that was now unlocking dreams. For in another flash and with overwhelming emotion came the realization that Berenice had been encountered, leaving a scattering of star-dust in her train.”

Some other random observations about Cornell: