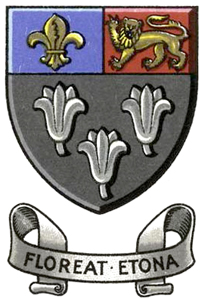

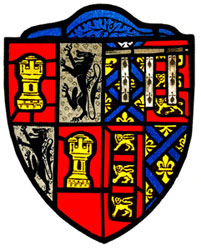

Medieval Shields ~ Shield in stained glass of the 14th Century of John of Gaunt as King of Castile

After a brief delay, I’m back again to finish sharing the introductory article to W. H. St. John Hope’s fascinating book Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers. If you want to start reading from the beginning, here’s the order: Part 1 – Heraldry, Part 2 – Coat of Arms, and Part 3 – Coat of Arms History. If you want all the pieces in one fell swoop, you can download a PDF of the article (minus the pictures) at the end of this post. Also, if you want to see and download the majority of the images from the book, visit the Public Domain Images at Karen’s Whimsy.

Now, without further ado . . .

Mr. St. John Hope continues:

Since the elucidation of the artistic rather than the scientific side of heraldry is the object of this present work, it is advisable to show how it may best be studied.

The artistic treatment of heraldry can only be taught imperfectly, by means of books, and it is far better that the student should be his own teacher by consulting such good examples of heraldic art as may commonly be found nigh at hand. He may, however, first equip himself to advantage with a proper grasp of the subject by reading carefully the admirable article on Heraldry, by Mr. Oswald Barron, in the new eleventh edition of The Encyclopedia Britannica.

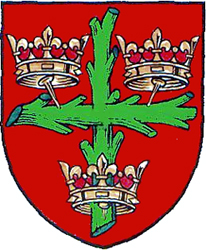

Family Crest Symbols ~ Seal of Henry Le Despnser, Bishop of Norwich, 1270 – 1406

The earliest and best of artistic authorities are heraldic seals. These came into common use towards the end of the twelfth century, much at the same time that armory itself became a thing of life, and they were constantly being engraved for men, and even for women, who bore and used arms, and for corporate bodies entitled to have seals.

Moreover, since every seal was produced under the direction of its owner and continually used by him, the heraldry displayed on seals has a personal interest of the greatest value, as showing not only what arms the owner bore, but how they were intended to be seen.

From seals may be learnt the different shapes of shields, and the times of their changes of fashion; the methods of depicting crests; the origin and use of supporters; the treatment of the ‘words’ and ‘ reasons’ now called mottoes; the various ways of combining arms to indicate alliances, kinships, and official connexions; and the many other effective ways in which heraldry maybe treated artistically without breaking the rigid rules of its scientific side.

Seals, unfortunately, owing to their inaccessibility, are not so generally available for purposes of study as some other authorities. They are consequently comparatively little known. Fine series, both of original impressions and casts, are on exhibition in the British and the Victoria and Albert museums, and in not a few local museums also, but the great collection in the British Museum is practically the only public one that can be utilized to any extent by the heraldic student, and then under the limitation of applying for each seal by a separate ticket.

The many examples of armorial seals illustrated in the present work will give the student a good idea of their importance and high artistic excellence.

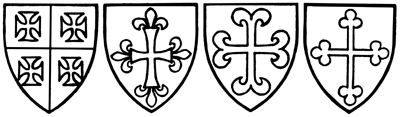

Heraldic Symbols ~ Shields of Dacre, Shelley, See of Salisbury, and Isle of Man

Next to the heraldry on seals, that displayed on tombs and monuments, and in combination with architecture, may be studied, and, of course, with greater ease, since such a number of examples is available. Many a village church is comparatively as rich in heraldry as the abbey churches of Westminster and St. Albans, or the minsters of Lincoln and York and Beverley.

It is to the country church, too, that we may often took for lovely examples of old heraldic glass, which has escaped the destruction of other subjects that were deemed more superstitious.

But the student is not restricted to ecclesiastical buildings in his search for good examples of heraldry.

Inasmuch as there never was such a thing as an ecclesiastical style, it was quite immaterial to the medieval master masons whether they were called in to build a church or a gatehouse, a castle or a mansion, a barn or a bridge. The master carpenter worked in the same way upon a rood loft or a pew end as upon the screen or the coffer in the house of the lord; the glazier filled alike with his coloured transparencies the bay of the hall, the window of the chapel, or that of the minster of the abbey; and the tiler sold his wares to sacrist, churchwarden, or squire alike.

The applications of heraldry to architecture are so numerous that it is not easy to deal with them in any degree of connexion.

Coat of Arms Pictures ~ Paving Tiles from Tewkesbury Abbey Church

Shields of arms, badges, crests, and supporters are freely used in every conceivable way, and on every reasonable place; on gatehouses and towers, on porches and doorways, in windows and on walls, on plinths, buttresses, and pinnacles, on cornice, frieze, and parapet, on chimney-pieces and spandrels, on vaults and roofs, on woodwork, metalwork, and furniture of all kinds, on tombs, fonts, pulpits, screens and coffers, in painting, in glass, and on the tiles of the floor (see above).

Though actual examples are now rare, we know from pictures and monuments, and the tantalizing descriptions in inventories, to how large an extent heraldry was used in embroidery and woven work, on carpets and hangings, on copes and frontals, on gowns, mantles and jupes, on trappers and in banners, and even on the sails of ships.

Wills and inventories also tell us that in jewelry and goldsmiths’ work heraldry played a prominent part, and by the aid of enamel it appeared in its proper colours, and advantage not always attainable otherwise. Beautiful examples of heraldic shields bright with enamel occur in the abbey church of Westminster on the tombs of King Edward III and of William of Valence, and on the tombs at Canterbury and Warwick respectively of Edward prince of Wales and Richard Beauchamp earl of Warwick; while in St. George’s chapel in Windsor castle there are actually nearly, ninety enamelled stall-plates of Knights of the Garter of earlier date than Tudor times, extending from about 1390 to 1485, and forming in themselves a veritable heraldic storehouse of the highest artistic excellence.

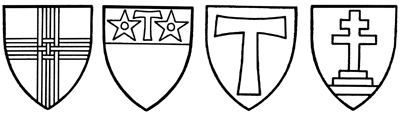

Heraldry Clipart ~ A Shield from a Roll of Arms from a Jousting Tournament

Another source of coloured heraldry is to be found in the so-called rolls of arms (see above).

While heraldry was a living art, it obviously became necessary to keep some record of the numerous armorial bearings which were already in use, as well as of those that were constantly being invented. This seems to have been done by entering the arms on long rolls of parchment. In the earliest examples these took the form of rows of painted shields, with the owners’ names written over; but in a few rare cases the blazon or written description of the arms is also given, while other rolls consist wholly, of such descriptions, as in the well-known Great and Boroughbridge Rolls. These have a special value in supplying the terminology of the old heraldry, but this belongs to the science or grammar and not the art of it. The pictured rolls on the other hand clearly belong to the artistic side, and as they date from the middle of the thirteenth century onwards, they show how the early heralds from time to time drew the arms they wished to record.

Click here to download a copy of the entire introduction to Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers by W. H. St. John Hope, published by The MacMillan Company, 1913.