Free Heraldry

This is the third part of a series of articles where I share the introduction to the book Heraldry for Craftsmen and Designers by W. H. St. John Hope. Mr. St. John Hope details the fascinating world of coat of arms history, explaining the rules that guided the creation of a coat of arms during the Middle Ages.

Mr. St. John Hope writes:

In the Great Roll of ams, of Edward II, are instances of two shields, in the one case of a red lion, and in the other of a red fer-de-moline, on fields party gold and vert; also of a silver leopard upon a field party gold and gules, and of three red lions upon party gold and azure. Likewise of a shield with three lions ermine upon party azure and gules, and of another with wavy red bars upon a field party gold and silver.

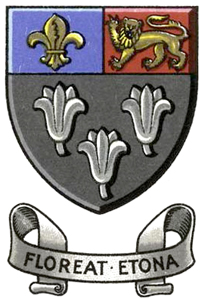

In the arms, too, of Eton College granted by King Henry VI in 1448-9, three silver lilies on a black field are combined with a chief party azure and gules, with a gold leopard on the red half and a gold fleur-de-lis on the blue half. King Henry also granted in 1449, these arms, party cheveronwise gules and sable three gold keys to Roger Keys, clerk, for his services in connexion with the building of Eton College, and to his brother Thomas Keys and his descendants. See below.

Coat of Arms of Eton College from Victorian Web

Shields with quarterly fields often had a single charge in the quarter, like the well-known molet of the Veres, or the eagle of Phelip.

Arms were sometimes counter-colored, by interchanging the tinctures of the whole or parts of an ordinary or charge or charges overlying a parti-colored field. This often has a very striking effect, as in the arms of St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, which are party silver and sable a cheveron counter-coloured or those of Geoffrey Chaucer, who bore party silver and gules a bend counter-coloured. Sir Rober Farnham bore quarterly silver and azure four crescents counter-colored, or as the Great Roll describes them, ‘de l’un en l’autre.’ the town of Southampton like-wise bears for its arms gules a chief silver with the three roses counter-colored.

In drawing party-colored fields it is as well to consider what are the old rules with regard to them. In the early rolls a field barry of silver and azure, or of gold and sable, is often described as of six pieces, that is with three coloured bars alternating with the three of metal, though barry of eight and even ten pieces is found. Paly of six pieces is also a normal number. But the number of pieces must always be even, or the alternate pieces will become bars or pales. The number of squares in each line of a checkered field or ordinary is also another important matter. Six or eight form the usual basis for the division of a field, but the seven on the seal of the Earl of Arenne and Surry attached to the Barons’ Letter of 1300-1 is not without its artistic advantages. On an ordinary, such as a fesse or cross, there should be at least two rows of checkers. Here, however, as in other cases, much depends upon the size of the shield, and a large one could obviously carry with advantage either on field or ordinary more squares than a small one without infringing any heraldic law.

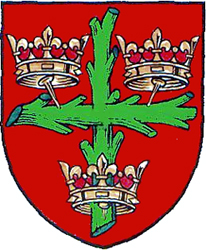

Arms of the town of Colchester with a ragged cross from Heraldry of the World

Besides the plain cross familiar to most of us in the arms of St. George, and the similar form with engrailed edges, there is a variety known as the ragged cross, derived from two crossed pieces of a tree with lopped branches. This is often used in the so-called arms of Our Lord, showing the instruments of His Passion, or in compositions associated therewith, as in the cross with the tree crowned nails forming the arms of the town of Colchester. See above.

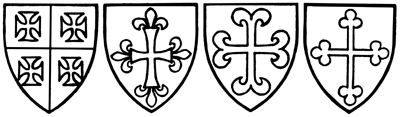

Several other forms of cross have also been used. The most popular of these is that with splayed or spreading ends, often split into three divisions, called the cross paty, which appears in the arms of St. Edward. It is practically the same as the cross called patonce, flory, or fleury, those being names applied to mere variations of drawing. The cross with les chefs flurettes of the Great Roll seems to have been one flowered, or with fleurs-de-lis, at the ends.

Another favourite cross was that with forked or split ends, formed of a fer-de-moline or mill-rind, sometimes called a cross fourchee, or, when the split ends were coiled, a cross recercelee. The arms of Antony Bek bishop of Durham (1284-1310) and patriarch of Jerusalem were gules a fer-de-moline ermine, and certain vestments “woven with a cross of his arms which are called ferrum molendini” passed to his cathedral church at his death. On his seal of dignity the bishop is shown actually wearing such a vestment of his arms. See below.

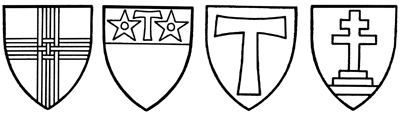

Heraldry Symbols

The tau or St. Anthony’s cross also occurs in some late fifteenth century arms.

The small crosses with which the field of a shield was sometimes powdered were usually what are now called crosslets, but with rounded instead of the modern squared angles, as in the Beauchamp arms, and a field powdered with these was simply called crusily. But the powdering sometimes consisted of crosses paty, or formy as they were also styled as in the arms of Berkeley, or of the cross with crutched ends called a cross potent, like that in the arms of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. These crosses often had a spiked foot, as if for fixing them in the ground, and were then further described as fitchy or crosses fixable.

To be continued . . .

May I ask you a queston?

Are you half Greek?

where did you get this inpho